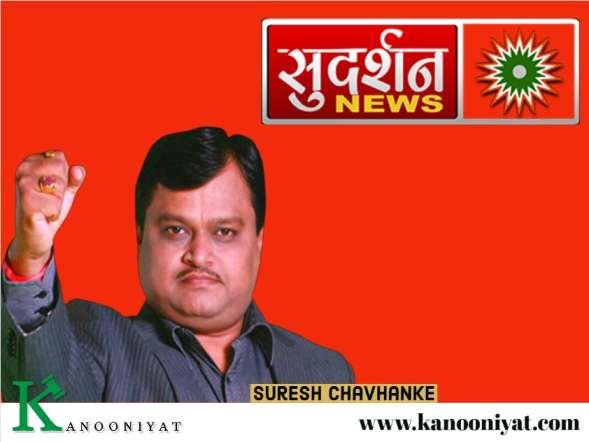

A bench of Justices DY Chandrachud, Indu Malhotra & KM Joseph heard a petition filed on the ground that it was communalizing the entry of Muslims into UPSC against the telecast of the show hosted by the Sudarshan TV ‘s Chief Editor Mr. Suresh Chavhanke, which was initially proposed on August 28.

The Supreme Court made some strong oral remarks taking objections in this regard.

“This program was so insidious. Citizens from a particular community who go through the same examinations and get interviewed by the same panel. This also casts aspersions on the UPSC examination. How do we deal with these issues? Can this be tolerated?”, Justice Chandrachud observed.

“…how rabid can it get? Targeting a community who are appearing for Civil services!”, exclaimed Justice Chandrachud

On September 10, the Centre allowed the telecast of the show, after observing that the content should not violate the Sudarshan Tv program code. Afterwards , the show was telecast on September 11.

Senior Advocate Shyam Divan that on the resumption of the hearing at 2.45 PM, he shall have to tell the court what he is planning to do.

“We expect some restraint from your client, will undoubtedly give you time. Your client is doing a disservice to the nation by doing what it is doing”, Justice Chandrachud told Shyam Divan.

The bench reflected upon the ramifications of how Electronic media can be used as a tool to threaten national security and stability and pondered upon the need for putting forth regulations.

“No freedom is absolute, not even journalistic freedom,” said Justice KM Joseph

While Senior Advocate Anoop Chaudhari appeared for petitioner Firoz Iqbal Khan stating that the show is “blatantly communal”, Senior Advocate Shyam Divan said that it was an investigative report of Sudarshan TV concerned with national security.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta pointed out that regulating media would be very difficult and that it could be disastrous for democracy. He also added that “rabid” things are often spoken from both ends, “I don’t want to get into the right and left wing of it,” he added.

“The petition had thus raised significant issues bearing on the ‘protection of constitutional rights’,” the bench of Justices DY Chandrachud & KM Joseph had observed.

“Prima facie, the petition raises significant issues bearing on the protection of constitutional rights. Consistent with the fundamental right to free speech and expression, the Court will need to foster a considered a debate on the setting up of standards of self- regulation. Together with free speech, there are other constitutional values which need to be balanced and preserved including the fundamental right to equality and fair treatment for every segment of citizens”, the SC said indicatied its intention to examine the issue in a larger perspective to lay down guidelines for broadcast of Sudarshan Tv.

The petitioner submitted that the airing of views in the course of the programme would violate the Programme Code enumerated under the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act 1995, together with the Code of Ethics and News Broadcasting Standards Regulations.

On drawing a survey of Indian Constitutional provisions, precedent and international and comparative constitutional law, intervenors point out that the following propositions for consideration:

a. Offensive speech is distinct from hate speech;

b. The Constitutional protects offensive speech but does not protect hate speech. Penal provisional such as sections 153A & 153 B of the IPC must be interpreted in a manner that keeps the distinction between the two intact.

c. Offensive speech is simply speech that causes subjective feelings of offence or outrage and nothing more. Such speech may be ill-considered, unwise and improper but it is not illegal.

d. Hate speech goes beyond subjective feelings of offence and objectively has the effect of undermining constitutional constitutional equality, sending a message that a person or a group of people are not worthy of equal concern of respect and are not equal members of society, or are fair game for discrimination, hostility or violence.

e. Determining hate speech, therefore, requires a contextual enquiry by judicial and other State bodies, looking (a) the actual words used, (b) the meanings that they carry for their intended recipients, (c) any history of similar language, (d) and the likely consequences.

f. Hate speech can be direct (calls to violence and discrimination), but it can also be indirect, through, insinuation, and what is popularly known as dog-whistling. This, therefore, requires judicial bodies to be sensitive to the nuances and specific histories of the speech in question.

g. The distinction between offensive speech and hate may be parsed with the help of following examples:

i) Criticism, mockery and ridicule of respected and revered religious or cultural figures may be offensive but it is not hate speech. Calling for a boycott of the members of a religious or cultural community or implying that they are violent by nature or unpatriotic by virtue of their community affiliation is hate speech.

ii) Mockery of religious beliefs or traditions may be offensive but it is not hate speech. Accusations of dual loyalties towards members of any faith – and suggestions of treachery by virtue of belonging to that faith – constitutes hate speech.

iii) Speech that has historically been inseparable from practices of oppression and subordination is hate speech (see eg. of this Hon’ble Court’s examination of the use the word “chamar”, under the Prevention of Atrocities Act, in Swwaran Singh Vs. State).